In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

The Star Beast is the story of young John Thomas Stewart XI, a boy who has inherited Lummox, a creature brought home from space by one of his ancestors. While Lummox is a good-natured family pet, the “pet” has grown to the size of a dump truck and is now seen as a threat to the community. While the book takes place on Earth, its main focus is on humanity finding its place among a galaxy full of alien races. It turns out Lummox holds a secret that brings Earth to the attention of a previously unknown alien race, one that is powerful and possibly dangerous. The story is full of twists and turns, with high stakes and fascinating characters.

At first glance, The Star Beast seems reminiscent of Heinlein’s earlier juvenile Red Planet, another story of a young boy with an alien pet who has completely misunderstood the pet’s true nature. However, in addition to the obvious differences in the size of the respective pets, Lummox’s story takes some unique and interesting turns along the way.

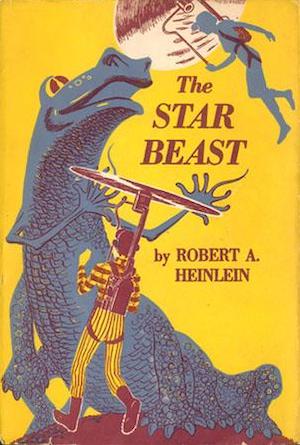

The Star Beast first appeared (under the title “Star Lummox”) as a serial in the May through July 1954 issues of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, and was then published later that year as a Scribner and Son’s juvenile. For this review, I used a Del Rey paperback reissue borrowed from my son, a Science Fiction Book Club omnibus edition entitled To the Stars, and an audio drama version from Bruce Coville and his Full Cast Audio team (those audio dramas, from the early 2000s, are well worth seeking out for fans of audible entertainment).

About the Author

Robert A. Heinlein (1907-1988) was one of America’s most widely known science fiction authors, frequently referred to as the Dean of Science Fiction. I have often reviewed his work in this column, including Starship Troopers, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, “Destination Moon” (contained in the collection Three Times Infinity), The Pursuit of the Pankera/The Number of the Beast, and Glory Road. From 1947 to 1958, he also wrote a series of a dozen juvenile novels for Charles Scribner’s Sons, a firm interested in publishing science fiction novels aimed at young boys.

These novels include a wide variety of tales, and contain some of Heinlein’s best work, including many works I’ve covered in previous columns: Rocket Ship Galileo, Space Cadet, Red Planet, Farmer in the Sky, Between Planets, The Rolling Stones, Starman Jones, The Star Beast, Tunnel in the Sky, Time for the Stars, Citizen of the Galaxy, and Have Spacesuit Will Travel. This is not the first time The Star Beast has been discussed on this site, as James Davis Nicoll mentioned it briefly last year in a column on “Five Tough, Rough, and Rugged Heinlein Stories.”

A Tale of Two Bureaucrats

Heinlein generally inserted some educational elements into his juveniles, touching on topics such as space travel, exploration, farming, revolutions, spacesuits, or other issues—a bit of didactic medicine mixed with the spoonful of sugar, if you will. In the case of The Star Beast, the author endeavors to educate his young readers about politics, to the point where the juvenile adventure sometimes disappears as the political characters take over the narrative. Some of that political intrigue will likely be lost on readers who don’t understand the difference between political appointees and career civil servants, and other aspects of bureaucratic organizations. Of course, politics has often been a major theme and focus of science fiction, and the online Encyclopedia of Science Fiction has a good overview of the topic here.

While Heinlein’s politics and beliefs shifted and changed over the course of his life, he often spoke and wrote about libertarian ideas, and those familiar with his work will not be surprised that the government of Westville, where young John Thomas lives, is portrayed as inept and filled with people who often let personal feelings and relationships drive their decisions. The exact location of the town is not specified, but it appears to be somewhere in the Rocky Mountains. At one point, an important decision seems to be made based on who has been fishing with the local judge most recently, rather than the merits of the issue. The head of the local police force, Chief Dreiser, while he means well, and even serves as a deacon in a local church, is quick to jump to conclusions, and at one point, decides to move ahead with a plan to execute Lummox as a public threat, even though he has been ordered not to take that action.

Contrasted with the clumsy local government of Westville, however, is a fairly effective Federation bureaucracy. And one bureaucrat in that world-wide government has become one of my favorite Heinlein characters of all time… He is introduced by his full title, which is a mouthful: His Excellency the Right Honorable Henry Gladstone Kiku, M.A. (Oxon,) Litt. D. honorus causa (Capetown), O.B.E., Permanent Under Secretary for Spatial Affairs. In keeping with the diversity of characters we see throughout Heinlein’s juveniles, Mr. Kiku is Kenyan, and offers a contrast to the parochial inhabitants of Westville. Mr. Kiku is not without flaws. He is fretful and prone to anxiety-related maladies like ulcers. He also has a lifelong phobia involving snakes that is triggered by tentacles, something that makes his job difficult when dealing with alien races. But he is wise, brave, and has the knowledge accumulated through a long civil service career behind him.

His competence stands in clear contrast to the politically appointed Secretary MacClure, who is a politician of the type seen in John Thomas’ home of Greenville, and who is clearly in over his head. It might seem that an effective character like Mr. Kiku would contradict the depiction of government officials as inept elsewhere in the novel, but Heinlein always favored effectiveness over doctrine, and celebrated competence and expertise wherever it was found. And while the necessity of qualified, capable civil servants is questioned or even mocked by some in anti-intellectual circles, they are often the glue that holds together many a governmental entity.

The Star Beast

The book begins from the viewpoint of Lummox, a large eight-legged alien creature who was brought home from an interstellar journey many years ago, and has lived with the Stuart family for generations. Lummox is hungry and bored. The Stuart home has a walled backyard, but Lummox is able to escape by squeezing through a section of beams—although it’s a tight fit, thanks to a recent growth spurt (brought about when Lummox devoured John Thomas’ Buick). After eating some of the neighbor’s rose bushes, as well as a stray dog that has been terrorizing the neighborhood, the hungry creature turns to the vegetables in a nearby truck farm. The owner shoots at the intruder, sending the terrified Lummox crashing through a pair of greenhouses. After running into town, Lummox is attacked by police, first cornered in the display window of a local department store, and then herded into a local viaduct. This sequence of over-the-top action suggests Heinlein might be in the mood for a slapstick satire, but the story soon settles into the more grounded and realistic style for which he is known.

We then meet high school senior John Thomas Stuart XI, Lummox’s owner, who is called upon to get his pet under control. He gets the news of the rampage from his mother, a fretful woman who has wanted to get rid of Lummox for years. She is a widow whose explorer husband was lost on a space voyage, and has been grieving ever since. Afraid to lose John Thomas to adulthood, she has been doing her best to ensure he sticks close to home and does not follow in the footsteps of his adventurous ancestors.

John Thomas is summoned by Chief Dressler to guide Lummox back home, and is joined by his girlfriend, Betty Sorenson. Betty is an extremely intelligent and self-assured young woman, confident enough that she’s divorced her parents and moved into government-provided quarters. While we don’t get Mrs. Stuart’s opinion of Betty, she must be horrified by her son dating someone so independent. Because the book is a Heinlein juvenile, there is no kissing or physical affection displayed between John Thomas and Betty; instead, they settle for mocking each other, name-calling, punching each other in the arm, and things like that. Betty exhibits her negotiating skills right from the start. There is a hearing scheduled to decide what to do about Lummox and how to deal with all the damage, and Betty takes the lead on arguments, tying the local magistrate, Judge O’Farrell, into knots.

The adventures of Lummox, and the mysteries surrounding the creature’s origin, reach the attention of Mr. Kiku, and he dispatches one of his Commissioners, Sergei Greenberg, to investigate. Sergei decides to assume jurisdiction for the Federation, and takes charge of the hearing. But Betty ties him in knots as well, and he ends up with a decision to destroy Lummox that will be held in abeyance until the creature’s origin can be investigated.

Mrs. Stuart, eager to resolve this issue, brings home a representative from a natural history museum, who offers to buy Lummox, keep him safely, and even offers John Thomas a job as an animal handler to keep the two together. Mrs. Thomas doesn’t like the animal handler part, as she wants John Thomas to go to college and study a nice, safe profession that will keep him close to home. John Thomas reluctantly agrees to the sale, but then changes his mind, and in the wee hours of the morning, heads out into the mountains with Lummox, following the path of an old-fashioned highway that has been abandoned and fallen into disrepair. He thinks he is being clever, but is soon joined by Betty, who deduces exactly where he is headed.

Meanwhile, Mr. Kiku is dealing with an alien race represented by an alien named Doctor Ftaeml, whose head tentacles unfortunately trigger Mr. Kiku’s phobias. The alien race is threatening Earth with destruction if they do not produce a member of their species who was kidnapped from their homeworld decades ago, and it doesn’t take Mr. Kiku long to realize that Lummox may be the object of their search. Meanwhile, orders to capture Lummox without harming him have gone awry, and Chief Dressler has put a bounty on his head. I will leave the recap at this point, as saying more would spoil some adventurous twists and turns that occur later in the book.

Before I end my discussion, however, I do want to address the female characters. The first is Mrs. Stuart, for whom I feel sorry. She is defined almost completely by her marriage, her son, and her grief. The men of the Stuart family have a proud heritage that includes explorers, warriors, and even a founding member of the Mars Republic. But her goal at every turn is to stifle any ambition shown by John Thomas, and keep him close to her. The only time we learn her first name, Marie, is in a court document, and no one ever refers to her by that name. While other characters move on to new roles, new jobs, and new adventures, she is afforded no such opportunity for growth, and is instead left only with her unresolved grief.

For different reasons, I also found Betty Sorenson’s portrayal problematic. She runs circles around John Thomas intellectually, and she constantly shows more initiative and confidence than he does. She is the one who negotiates most successfully with Misters Greenberg and Kiku. Yet it is clear throughout the book that her main goal in life is to support John Thomas and make him happy. Their relationship does not feel like a partnership, and certainly not one between equals. Heinlein’s juveniles often show wives subordinating themselves to their husbands, and it is irritating to see such a promising character starting that trajectory at a young age.

Final Thoughts

The Star Beast, while not one of my favorite Heinlein juveniles, ranks in the upper half of those books, at least in my humble opinion. The sections dealing with politics, which went over my head as a youth, were the best part of the book when reading as an adult. And Mr. Kiku has shot up the ranks to become one of my favorite Heinlein characters of all time. The one complaint I have with the book, which is a problem I’ve had with other Heinlein juveniles, is the way female characters are portrayed. It’s a shame that Heinlein, while doing an excellent job of portraying other types of diversity in his juveniles, did such a poor job with gender roles.

And now it’s your turn to talk: I’m interested in your thoughts on The Star Beast in particular, or Heinlein’s juveniles in general. And if there are there any other YA stories on the topic of alien pets that you think are worthy of mention, I’d enjoy hearing about them.

Typo, I think.

Could it be that Betty, like Lummox, has taken up the hobby of raising John Thomas Stuarts? That might explain her goal of promoting his happiness and well-being.

I found it interesting that Heinlein does not expand much upon Lummox’s inner life except in the simplest of terms (if I recall correctly – this is one of those juveniles that I read when I was a juvenile myself). It gave the sections devoted to Lummox more or less on her own the quality of good animal-centred writing – Ernest Thomas Seton comes to mind, or Gerald Durrell.

Another thing that I wondered about when I read the book was what sort of protocols Terran explorers observed on newly discovered planets. I’d think that the last thing anyone would be allowed to do would be to pick up and carry off as a souvenir an unknown animal, regardless of how appealing it was.

Heinlein tended to assume that spaceships would be like the US Navy he knew. He was probably aware that (a) seamen were apt to pick up interesting things and (b) wise officers didn’t fuss about this unless there was trouble. (“A wise man does not concern himself with trifles” shows up as late as Job.) (He also knew that apparent trifles sometimes weren’t — cf the flatcats in The Rolling Stones — but would have come down on the side of not trying to enforce rules for everything.) The rules Alan mentions would probably have pertained more to good order than, e.g., the noninterference doctrine of Star Trek.

I wonder whether this book could be published today, if only because of all the mood-altering pills Mr. Kiku keeps popping. He is one of my favorite Heinlein characters, though: a (gasp) government bureaucrat who gets things done and is a force for good!

Raskos, There was a passage in the book explaining how the John Thomas who brought Lummox home was breaking all the rules by doing so.

Thank you, Alan.

Good to read your review. This is one of my favourite Heinleins, even now.

My copy didn’t survive the great cull, probably for the reasons you describe. (Alas, that means I can’t check the number — I would have sworn the lead was JTS XXIII, despite Wikipedia. I also can’t check the name of the police chief, which you give as both Dreiser and Dressler.) But I remember this as a fun read even though I came to it as an adult. I wonder how much of RAH’s view of woman-as-hearthkeeper-and-reproducer (and if necessary manipulator to make those happen) was ingrained early, how much came from the ultramasculine culture of the Navy he knew, and how much was his resentment of not having children (which becomes more obvious in his later books). It does stick out now in ways that I didn’t notice 50-60 years ago.

Betty starts as a strong character, and does fade a bit toward the end, with apparently no professional ambitions of her own. Heinlein’s adult females could be quite capable and even occasionally put careers ahead of supporting their menfolk, e.g. Dr. Edith Stone in the Rolling Stones, but young women were largely absent or subordinate in his juveniles. I’ll give a pass for Pee Wee in Have Spacesuit, Will Travel, because she’s much younger than Kip— and is still a force to be reckoned with. The young women in Tunnel In The Sky are also quite competent. But in most of these books, young women are 2 dimensional, at best enigmas (e.g. Farmer in the Sky), or missing altogether. Part of this can be attributed to the limited viewpoints of the adolescent male protagonists, many of whom are still in what we call the “rock throwing stage” of interacting with their female peers. There is no excuse possible for Podkayne of Mars, however. I can only interpret that one as a book about Clarke that happens to be told from Podkayne’s point of view, simply because Heinlein had been challenged to write a book from a female point of view.

Well, given the definition that the protagonist of the book is the character who is most changed by the events of the plot, Clark Fries would clearly be its protagonist.

I have to say that I find The Star Beast one of Heinlein’s lesser juveniles, though on the other hand I find the juveniles his best single body of work and better than most science fiction for any age. On the other hand, I do admire the portrayal of Henry Kiku, especially his scene standing in the wind with Dr. Ftaeml, and I have to say it’s striking that Heinlein makes a career civil servant—a bureaucrat—effectively the hero of this novel! I don’t think I fully understood Kiku’s political situation when I first read this, but I was in elementary school at the time . . .

I think better of Betty Sorensen than you seem to. On one hand, she has goals of her own, and pursues them without consulting John Thomas, and whether or not they are things he cares about: See her negotiation with Kiku about John Thomas’s title in the mission to the Hroshii, where she demands rank and pay for him that he clearly doesn’t care about. On the other hand, she makes a clear moral choice that is not manipulative, in a moment of crisis, when John Thomas insists on staying with Lummox—and she insists on staying with John Thomas, despite the price she expects to pay. I think she makes the book a lot more lively. Imagine taking her out of the narrative: Doesn’t what remains seem a bit drab?

Um.

I would point out that what you call ‘goals of her own’, as described, still revolve around John Thomas – in this case, she is asking for rank and pay for John Thomas, even if he doesn’t want them.

True ‘goals of her own’ would involve things that would benefit her, not John Thomas. (And if someone tries to argue that she’s arguing for rewards for John Thomas as a thing that benefits her… that means she’s defining herself in terms of John Thomas instead of her own welfare, and that’s at least as bad.)